Escaping the Cave: Reflections on Truth and Reality

On Plato’s Theory of Forms, the Cave, and Why Our Worldview Matters

Each essay is paired with a 500-word Reflection Journal—an analytical summary—followed by a deeper exploration combining lessons from the reading with personal insights.

What is Reality?

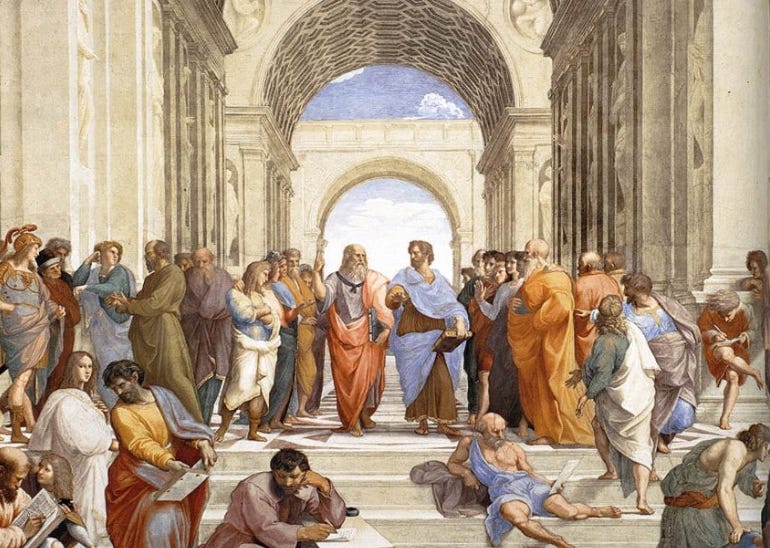

Plato’s Theory of Forms offers a unique existential perspective—one in which objective reality is derived from the ultimate truths of existence. The Allegory of the Cave, however, challenges us to compare our subjective perception of reality to the objective reality revealed by the Theory of Forms. This forces us to ask: Do we see the world as it is, or is the world only as we perceive it?

Through careful deliberation, we arrive at a fundamental realization—there are undeniable truths in the world, labeled as Forms, that shape every decision we make. This is the highest intelligible realm, the lens through which the clearest version of reality can be seen—a reality where we shape the world.

At the other end of the spectrum lies imagination and belief. Here, the world shapes us. At this level, reality is as subjective as it gets. To break free from this lower realm, we must climb the ladder of intelligibility and understanding.

For those deprived of intellectual curiosity, reality remains a deeply subjective experience. But for those who seek truth, reality becomes increasingly objective. The path to freedom from subjectivity begins with curiosity.

Yet for those unaware of their intellectual limitations, one question lingers—does it really matter?

At the very bottom of each essay, there is a simplified version for those looking for something less comprehensive and easily digested.

Objective: To understand the role that objective truth plays in our beliefs and how they shape our worldview.

Beyond the Shadows: Plato's Theory of Forms and the Nature of Reality

I. The Nature of Forms

A. Forms as Eternal, Necessary, and Independent Truths

Plato’s Theory of Forms insists that the ultimate truths of reality are of the highest level of knowledge, and all of our judgements are made in consideration of those truths. The truths Plato discusses exist objectively as eternal forms. They are not created by man but can be realized through reason, and knowledge of them is innate to human nature. However, innate truth does not imply conscious understanding—and that which is left to the subconscious can be a burden to the conscious. Not to be confused with Freudian subconscious desires that manifest as a Will to Pleasure but rather, the questions about the world that remain unanswered.

Our understanding of these ultimate truths determines how we see the world, and ultimately, how we live. If our view of the world is wrong or jaded, our lives will feel unclear. In other words, the revelation of these truths—answers to these questions—is necessary for a cohesive, productive worldview and while we’re at it, a sound conscience.

B. Forms as First Principles

These Forms, as first principles and ultimate truths of reality, are such that their essence is inseparable from their existence—Forms are not contingent but necessary realities. Their existence does not depend on anything else, yet they ground all that is knowable. The Form of the Good, like the sun in Plato’s analogy, illuminates the intelligible realm, making knowledge possible. Just as the sun enables sight, the Good enables understanding. To grasp this more deeply, we turn to Thomas Aquinas, who, drawing from Plato’s student Aristotle, observes: ‘A thing is said to be hotter as it more nearly resembles that which is hottest’—the truest form. In the same way, something is said to be good in proportion to how closely it participates in the Form of the Good, the highest reality from which all lesser goods derive their nature. (Summa Theologica I, Q2, A3)

II. The Ladder of Intelligibility

A. The Four Levels of Knowing

To recognize the Forms, one must ascend the hierarchy of intelligibility—from the visible to the invisible, from imagination to belief, then to thought, and finally, to true understanding. This progression may seem straightforward in theory, but in practice, it is anything but. Its complexity is exposed by a simple yet profound question:

'What is good?'

B. The Struggle of Understanding

Most people will struggle to answer. Why? Because they remain trapped in belief or thought, never progressing to true understanding. They accept what they think is good but lack the clarity to know why they think it. While many people behave as if they understand what is good—an argument in favor of the Forms' inherent nature—the proof that they do not is in this hypothetical response:

‘Because it is good.’

C. Levels of Understanding and the Square Analogy

To grasp this lapse in intelligibility, consider a layman’s scenario inspired by Plato’s example of geometry. A reflection of a square appears in a pond, and a bystander is asked:

'What is that?'

He responds, 'A reflection.'

This is Level 1 of understanding.

Then he is asked, 'What is it a reflection of?'

By his imagination, he believes, 'It’s a reflection of a square.'

He has progressed to Level 2.

Now, he holds an image of a square in his mind and he draws it.

This is Level 3 of understanding.

When asked how he knows to draw a square the way he did, he replies, 'Because that is what a square looks like.'

D. The Role of Forms

Yet in this response, something remains implicit. His thought of the square is not an invention, but a recognition—a trace of a first principle, an ideal form he has never seen with his eyes but knows in his mind. This is what Plato would call the Form of the Square. And yet, he does not fully understand it; he merely relies on it.

Now, apply this to Goodness. An event occurs, an action takes place—something is deemed good, though not yet determined to be so. Suddenly, an opinion assigns goodness to it. But why?

At Level 3, the explanation remains circular: 'Because things of that nature are thought to be good.'

But this begs the question—why are they thought to be good?

This is the final rung in the ladder of understanding: Level 4. To ascend it, one must not only recognize instances of goodness but grasp the principle itself. Just as one must reach beyond imperfect sketches of squares to understand what 'Squareness' truly is, one must rise above habitual judgments to comprehend Goodness in itself. When this effort is made, what was once a passive attribution of goodness transforms into conscious knowledge of the Form of the Good. And in that moment, one does not merely believe in Goodness—one understands it.

Why is this important?

III. Why Reality Matters

A. The Existential Cost of Stopping at Belief

This may seem like a rhetorical question—‘Why does reality matter?’—doesn't it? Yet, I’ve asked it twice now, and for good reason. Many assume the importance of reality is self-evident: we live in it, and that alone makes it important. And on the level of ordinary belief—Level 3 understanding—that answer suffices. But for those of us who now grasp Plato’s Forms and have glimpsed Level 4 understanding, such an answer will no longer satisfy us. In fact, it will leave us empty.

B. Why do we seek Truth?

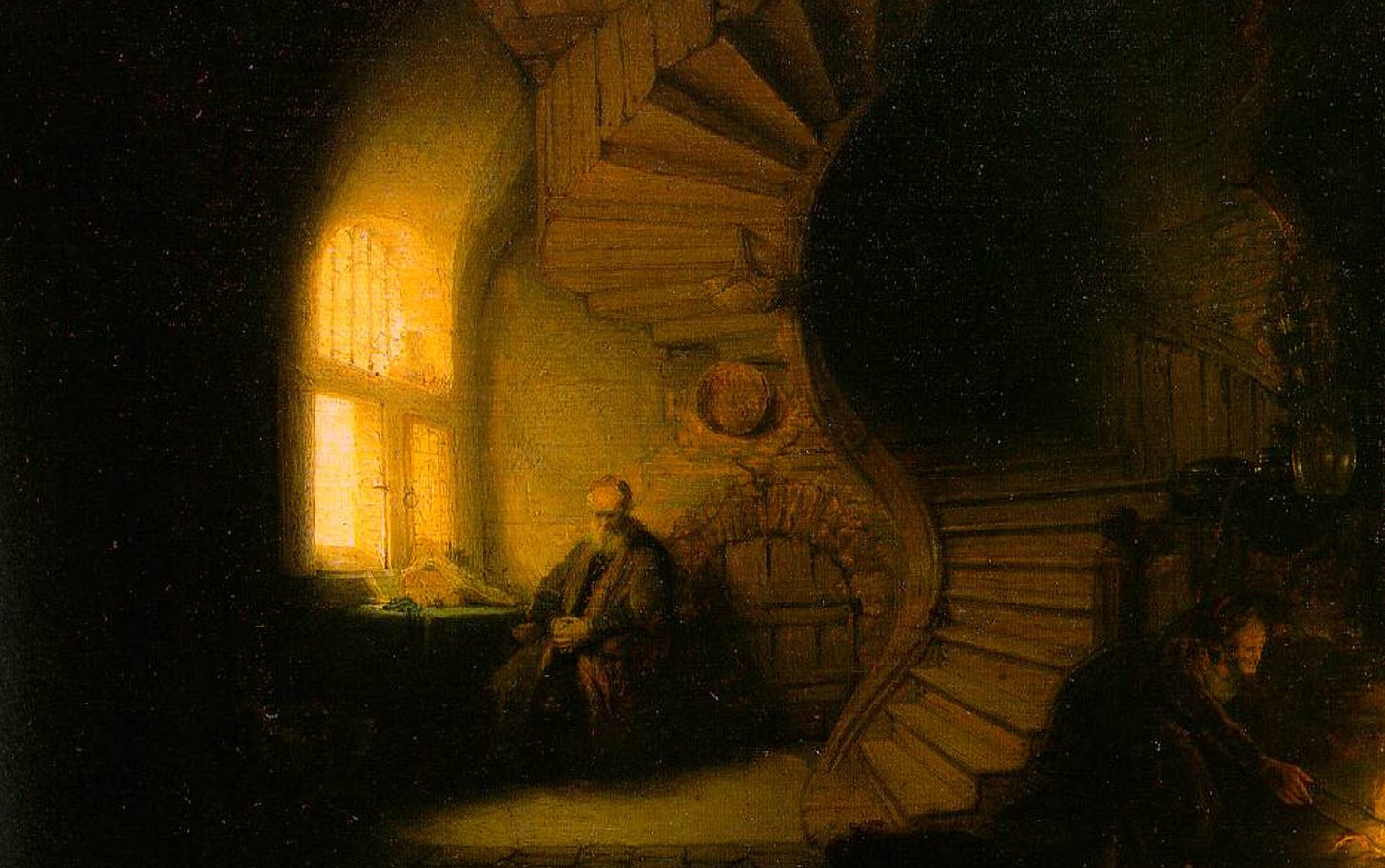

We know, in our nature, that the Forms exist. If we stop at mere belief, our subconscious senses the incompleteness—an unresolved question buried beneath the surface. This tension manifests in the conscious mind as a lack of direction, leading first to confusion, then to carelessness, and finally, to a misguided pursuit of something that feels like truth but is not.

C. Mistaking Shadows for Reality

To see where this path leads, we turn to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. If we remain at Level 3, we do not truly understand reality—we assume it. And when beliefs—not truths—are our guide, we become like prisoners staring at the cave wall, mistaking shadows for reality. The truths of reality are what guide us when we are lost. If we fail to grasp them, we are left with nothing but illusions to navigate the world. And illusions, no matter how familiar or comforting, will never lead us to freedom.

D. The Choice Between Truth and Comfort

So, is the world we see an accurate reflection of reality—or is it all a lie? One of Plato’s greatest questions forces us to confront this possibility. Are we, like the cave-dwellers, mistaking shadows for truth?

Of course, we all imagine we’ve left the cave—that we live in the light, grounded in reality. But how can we be sure? Can we be sure? More importantly—do we even want to be? What happens when we realize we are still in the cave, and the world we thought was real is nothing more than flickering illusions?

This is the unsettling doubt that seeps in when we fully grasp the implications of the Allegory of the Cave. Only the one who steps into the light, blinded and overwhelmed, can understand the sheer weight of the truth. The foundation of his entire life begins to crumble beneath his feet. He faces a choice—stand firm in this new world, no matter how painful, or retreat into the shadows, where everything is familiar and safe.

Which will it be—truth, or comfort?

IV. The Nature of Comfort

A. The First Stage of Comfort — Default Ignorance

Comfort is an interesting state of experience. It exists in three ways.

First, comfort is a default state—born from ignorance. It exists simply because it always has. This is the case for cave-dwellers who have never left the cave and, more importantly, have never thought to leave. Because they have never glimpsed anything beyond their world, they feel no pressure to seek anything more. Their comfort is not a choice, but a condition of existence. This changes the moment truth is introduced.

B. The Second Stage of Comfort — A Retreat from Truth

Suddenly, comfort stands in the opposition of truth—it becomes a safe haven to retreat to. This is the second form of comfort (to which we will return). When the cave-dweller steps into the light, comfort is no longer an unconscious state but a conscious option. This is where most of us reside. We know there is something closer to truth, because we have seen glimpses of it or entertained the thought, yet we choose to remain in comfort. We step outside, only to retreat. However, if we step outside just a few more times, comfort transforms again.

C. The Third Stage of Comfort — Becoming Comfortable with Discomfort

The final stage of comfort is born from an affinity for discomfort. The blinded cave-dweller, struggling in the unfamiliar light, slowly adjusts. Over time, discomfort itself becomes familiar. Eventually, he transforms into a seeker—no longer content with the shadows, now driven to uncover what lies beyond them. In this state, the pursuit of truth becomes second nature, and what was once foreign—discomfort—becomes the new default. Only now, the bar has been raised. This level of comfort is the ultimate freedom. In a way, discomfort ceases to exist.

Unfortunately, many of us will be deprived of the third level of comfort. Why? What is it that prevents our leap to the second level? What would prompt a cave-dweller to look over his shoulder, away from the shadows?

V. Curiosity vs Comfort

A. Curiosity as The Beginning of Progress

Curiosity is the greatest impetus for human progress. From the moment we enter the world, a craving for answers propels us forward. As infants, everything around us is a question. As we grow, our curiosity continuously reshapes our ever-evolving worldview. In a state of constant inquiry, we learn to embrace the unknown and become comfortable with discomfort. We begin our lives in this third level of comfort, the ideal level.

B. When Curiosity Dies

But if curiosity ceases, we fall prey to our environment. Our minds stagnate, and instead of shaping the world, we become shaped by it. Soon, we disengage from reality, and the evolution of our worldview comes to a halt. We enter a reactionary state, where our actions are no longer driven by deliberate thought but dictated by habit and conditioning. Rather than acting on the world, the world acts on us—on our minds, our bodies, and our very sense of self. Slowly, our personhood collapses into our nature. The Self dissolves as it surrenders control to physiology and psychology. This is how we become trapped before reaching Level 4 Understanding. That is the danger of comfort. That is why we can never lose our curiosity.

C. Why We Stop at Belief

The reason a cave-dweller knows that shadows exist but not why is simple. Their curiosity stopped at the first answer. At some point, they asked, 'What are these black shapes that move all around me?’ And an answer was given: shadows. It was enough. From that moment on, they had a name for their world. A satisfactory explanation. And so their curiosity ceased to exist. The shadow world became familiar, and comfort settled in.

But is that really such a bad thing?

VII. Is Comfort Dangerous?

A. Defining Comfort — Freedom from Pain

Yes, in the grand scheme of things, comfort is dangerous. To understand why, we must define it: comfort is a state of physical ease or freedom from pain and constraint. At first glance, this doesn’t seem bad. What’s wrong with being free from pain?

B. Comfort as a Vice

The problem is that comfort, like a drug, is addictive. Drugs take away pain. But too much of them, and the cure becomes worse than the disease. The same is true of comfort. Too much comfort, and the very life we sought refuge from begins to unravel into chaos. Comfort, like a drug, is not meant to be abused. If we exist in a constant state of comfort, our lives don’t just remain the same—they decay.

C. Comfort as The Enemy of Growth and Change

Now, don’t mistake comfort for a conflict-free life. The man who wakes up, argues with his wife every morning, goes to work, maybe stops by the gym, eats a microwaved meal, and hates his life but does nothing about it—he has grown comfortable. Not because he is happy, but because breaking the cycle would require more effort than enduring it. Comfort, in this sense, is not about pleasure; it is about stagnation. It is the opposite of change, the opposite of action. And that is dangerous. It means choosing inertia over transformation, familiarity over possibility. It means staying in the cave and watching the shadows, not because they are fulfilling, but because leaving would be too much work.

VIII. Escaping the Cave

A. Moving from Level 3 to Level 4

For the man to break the cycle and the cave-dweller to leave the cave, a leap from Level 3 to Level 4 Understanding is necessary. This is where Plato’s Theory of Forms and the Allegory of the Cave come full circle. Moving from Level 3 to Level 4 means no longer accepting borrowed beliefs to explain the world, but instead, seeking Truth itself.

B. Reviving Curiosity

To become a seeker, as we were when we first entered the world, curiosity must be revived. And with it, our attachment to comfort must dissolve. Curiosity disrupts complacency. It compels us to step into the unknown. The cave-dweller and the man will begin to question everything—who they are, why they are, where they are. The same scrutiny will extend to their circumstances, their choices, and the world itself. If they follow this path, it will lead them to Plato’s Forms—the ultimate truths of reality.

C. The Role of Discomfort in Understanding

Of course, this journey will be uncomfortable. Any journey into the unknown is. But prolonged exposure to discomfort leads to Level 3 Comfort—the ideal comfort. In time, the cave-dweller and the man will not just tolerate discomfort; they will embrace it. It will become second nature, driving them ever forward in pursuit of wisdom.

D. Freedom Through Seeking, Not Certainty

Ultimately, their worldview will begin to evolve again as they uncover deeper truths about reality. They will be freed—not by certainty, but by ignorance itself. Every unknown will become an invitation to expand their knowledge. And with each discovery, they will move further from the cave, not just into the light—but into the limitless pursuit of truth.

Plato’s Cave & The Search for Truth

(Simplified for Everyone)

What is Reality?

Plato’s Theory of Forms gives us a way to think about reality. It suggests that the world we see isn’t the full picture. Instead, there are deeper truths that exist beyond what we experience. These truths—called Forms—are like perfect ideas that shape everything around us.

The Allegory of the Cave helps us compare what we think is real to what actually is real. It forces us to ask:

Do we see the world as it truly is, or only as we believe it to be?

When we start thinking deeply, we realize that there are certain truths that don’t change—like justice, beauty, and goodness. These truths influence everything we do, whether we realize it or not. But most people never stop to think about them. Instead, they accept what they see at face value.

So, how do we go beyond our limited view of reality? How do we move from believing things to truly understanding them?

The Journey to Understanding

Plato believed that understanding reality is like climbing a ladder. We start at the bottom, where everything is based on imagination and belief—we just accept what we see without questioning it. At this level, we are shaped by the world around us.

But as we start asking questions, we begin to think for ourselves. The more we seek truth, the more we shape the world, instead of letting the world shape us.

For people who never question their reality, life feels simple. But for those who ask questions, life opens up in a whole new way.

So what happens if someone never questions anything? Does it even matter?

Why Does Reality Matter?

At first, reality seems obvious. We live in it, so it must be important, right?

But the truth is, most of us don’t actually see reality—we assume it. We go through life following what we’ve been told, never thinking deeper. But deep inside, we still feel something is missing. When we don’t understand the big questions, we feel lost. We might not realize it, but we start feeling confused, restless, or even frustrated.

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave shows what happens when we live in ignorance. If we never question what we see, we might be like prisoners in a cave, mistaking shadows for reality. But if we are willing to seek the truth, we can step outside and see the world as it really is.

The Danger of Comfort

Comfort is a tricky thing. It exists in three ways:

The First Level – Default Comfort

This is the comfort of ignorance. It’s when someone never questions their world because they’ve never even thought to. They don’t seek more, because they don’t know there’s more to seek.

The Second Level – Comfort as a Choice

At some point, a person might catch a glimpse of the truth. They realize there’s more to life than what they’ve known. But instead of chasing it, they choose to stay comfortable.

The Third Level – Comfort in Discomfort

This is where true growth happens. The person starts to embrace the unknown. They stop fearing discomfort and begin seeking wisdom, even if it’s difficult. Eventually, discomfort becomes normal—and this is the greatest freedom of all.

Most people never reach the third level. Why? Because it’s easier to stay where we are than to challenge ourselves.

So what makes someone turn around and question their reality?

Curiosity vs Comfort

Curiosity is what drives human progress. When we were children, we asked questions about everything. But as we grew up, many of us stopped asking.

Why?

Because curiosity is uncomfortable. It makes us rethink things we thought were certain. It forces us to change our worldview, and change is hard.

But if we stop being curious, we stop growing. Instead of shaping the world, the world starts shaping us. We become passive—living on autopilot, going through the motions. Over time, we lose our sense of self. We become trapped in Level 2 Comfort, afraid to step beyond what we know.

The reason most people accept their reality without question is simple: they got an answer once, and they stopped looking for more.

But is that really so bad?

Is Comfort a Bad Thing?

At first, comfort seems harmless. Who wouldn’t want to be free from pain?

But comfort is like a drug—it can make us numb. It takes away struggle, but also takes away growth. Just like taking too much medicine can cause more harm than good, too much comfort can lead to a life of stagnation and emptiness.

Some people think comfort means happiness. But imagine someone who:

Argues with their spouse every day

Works a job they hate

Eats the same meal every night

Knows they’re unhappy but never changes

That person isn’t happy, but they’re comfortable enough not to change. They’ve accepted their life as it is—because changing it would take effort.

That’s the real danger of comfort—it keeps us from action.

Escaping the Cave

So how do we break free?

Plato’s Theory of Forms and the Allegory of the Cave show us the way. If we want to reach the highest level of understanding, we have to stop accepting borrowed beliefs and start seeking truth for ourselves.

This means:

Reviving our curiosity—returning to the mindset we had as children.

Letting go of comfort—being okay with the unknown.

Asking hard questions—even if the answers are unsettling.

Yes, this path is uncomfortable. Yes, it’s uncertain. But the longer we embrace it, the stronger we become. Eventually, what was once difficult becomes second nature.

The man who leaves the cave doesn’t fear the unknown anymore—he seeks it.

Truth is not a choice. It is not a destination. It is an unraveling. (Kapil Gupta MD)

Basically, I agree with your platonic POV. The moment one sees beyond the veil, there is no returning. To seek comfort is to seek delusion. To seek Truth is to abandon all that once provided you comfort, standing raw/naked in the face of reality itself.

Great read and more relevant than ever. The elite ruling class can utilize their power to maintain the masses inherent desire to stay in the comfort zone. An example, most health ailments can be fixed through proper sleep, nutrition, and excersize. Yet to master those three components takes repeated steps outside of the comfort zone. Without the willingness to continue stepping out of the cave, leads one back into the quick fix- which always comes with negative side effects. We currently live in a climate of the highest levels of stress, depression, anxiety, obesity, etc… whilst also living in what id argue to be one of the most comfortable times. Satiating food for cheap on every corner, mental health days for when the going gets tough, unlimited entertainment for easy dopamine hits to avoid sitting in deep thought with oneself etc…

Question everything.